Baudin’s the ‘invisible bird’: a threatened species losing its identity

"I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me..."

So says the un-named protagonist in Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, a novel concerning the human struggle to find truth and identity in the face of racism. Many of the book's themes are relevant to the current human struggle to find truth and identity in the natural world, a struggle termed ‘speciesism’. Sometimes described as the ‘last frontier’ of discrimination, speciesism occurs where individuals of one species are treated differently to another simply due to our perceptions of those species.

Designations of conservation status and taxonomic distinctiveness (human constructs) are commonly thought to encourage conservation effort for individual species. So where does that leave species that are similar in their conservation status and biology?

To investigate this question, we identified several matched pairs of Australian threatened bird taxa where, despite both taxa in a pair being almost identical in their appearance, biology and ecology, one of the pair receives significantly greater levels of local and institutional support than the other. We studied three of these pairs to explore how a range of social factors, including stakeholder attitudes and institutional, policy and operational aspects might affect conservation efforts for particular species of threatened birds (Alligator Rivers and Capricorn yellow chats; Orange-bellied and Swift parrots; and Baudin's and Carnaby's black-cockatoos).

Among other things, this revealed that species receiving most conservation investment tend to be: encountered by a broad cross-section of the human community; considered iconic or charismatic; promoted as flagships; are rare, threatened or uncommon; or have a positive public profile.

Just like Ellison’s invisible protagonist, species can become invisible in the eyes of those making political decisions about them as they become overshadowed by the social context within which they inadvertently exist, their value framed by the attitudes of humans struggling to see the truth of their identity.

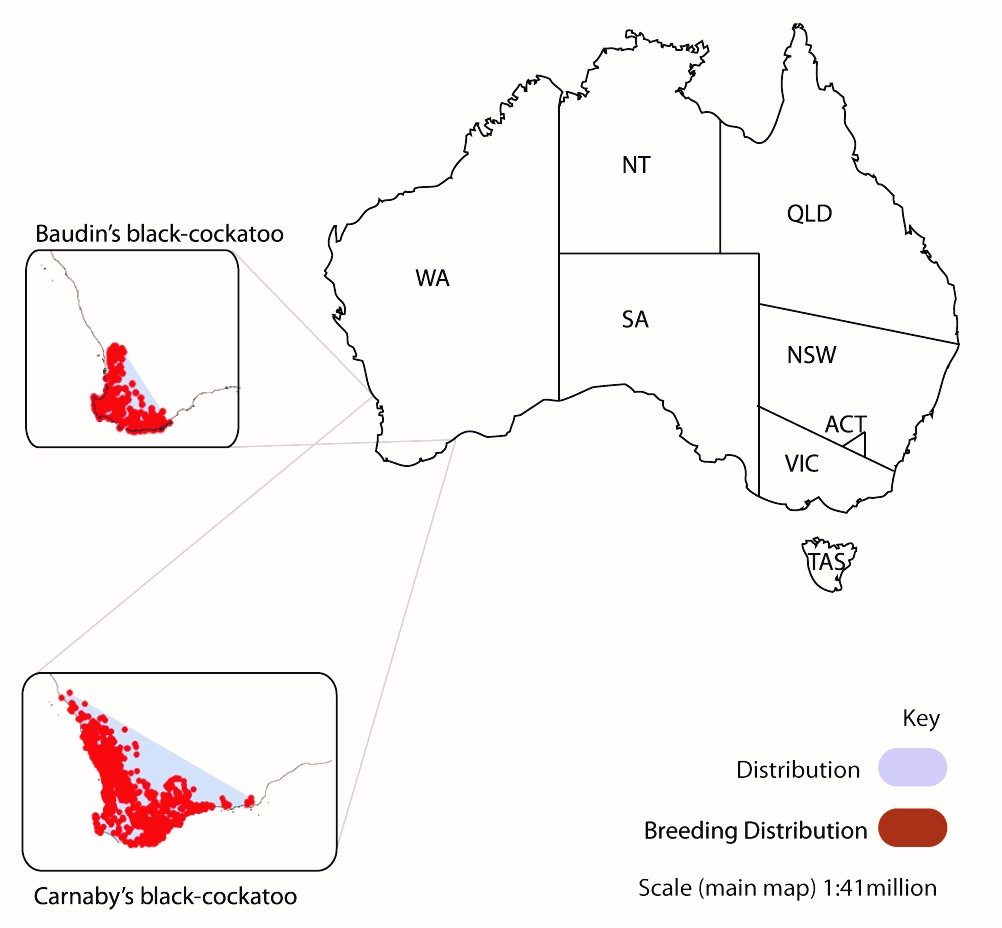

Take the case of Baudin’s (Calyptorhynchus baudinii) and Carnaby’s (C. latirostris) black-cockatoos, two rare and almost identical Australian species of white-tailed black-cockatoos. Both species are endemic to South-West Western Australia (WA) and both are listed as ‘rare or likely to become extinct’ under the WA Wildlife Conservation Act 1950. Their ranges overlap and they sometimes mingle when feeding so are commonly mistaken for a single species – usually Carnaby’s which are more common (~40,000 individuals) than Baudin’s (10,000 – 15,000).

Nevertheless, the birds differ in their calls and breeding and feeding behaviour (Chapman 2008). They are ecosystem engineers: just like Darwin’s finches, their bills are specifically adapted for their particular habitats. Baudin’s has a long, narrow bill perfect for removing seeds from Marri fruit, while Carnaby’s is a more adaptable generalist due to its shorter, broader bill.

Baudin's relationship with humans got off to a shaky start. Research confirms that the type specimen of Baudin's, collected by naturalists aboard Nicolas Baudin's South-West expedition in 1801, is actually a specimen of Carnaby's. Confusion arose partly because the specimen was illustrated and named by Edward Lear in 1832, whose tendency to overemphasise the upper mandible length of birds was a trademark of his artwork. At this time, it was generally thought that both cockatoos were the same species – the white-tailed black-cockatoo.

Baudin’s is further disadvantaged because it nests high up in mature forests in the humid and sub-humid zones. Since the 1950s, forests across the South-West have undergone intensive clearing reducing habitat and forcing both species to seek alternative sources of food and shelter. They were soon considered pests in pine plantations (Carnaby’s) and orchards (Baudin’s), attracting attention from scientists at a national research agency (CSIRO) in the late 1960s. A bounty on Baudin's was in place between the 1950s and the 1980s and orchardists can still obtain shoot to scare permits to protect their crops, despite netting being more effective. Baudin's remains a Declared Pest of Agriculture. Some orchardists lose around 8% of their net income to hungry flocks which leave orchards carpeted with guillotined, seedless apples. Consequently, 200-300 birds are illegally shot every year, significantly impacting on ageing populations of this long-lived species.

By 1979, Baudin's and Carnaby's were considered two full species, although research efforts and conservation resources have focused on the latter. Existing away from human habitation and difficult to encounter or study, Baudin's was invisible and overlooked. Living in Perth and its environs, Carnaby's was highly visible and became part of the social fabric; it invokes strong emotions influencing politicians and creating a virtuous circle of scientific research and public support. Despite appeals from conservation organisations, the public outcry for Baudin’s is modest compared to the alarm expressed at the loss of Carnaby's.

Baudin’s may soon be shot into extinction.

As Ellison's Invisible Man continues:

"When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves or figments of their imagination. Indeed, everything and anything except me."

Can Baudin’s exist when we struggle so hard to see it? Conserving our natural word is a difficult and complex undertaking and to do so we need greater understanding of not simply the natural world but also the social contexts we construct for its flora and fauna. If we do not, Baudin's will not be the last species to become truly invisible, right before our eyes.

Add new comment